In Spain, experiments on mice have proven the effectiveness of nanorobots; and in the US, scientists are testing promising immunotherapy medications and combinations of anti-tumor drugs. What has happened recently on the frontline of the fight against urothelial carcinoma? The article has a current digest of the most notable advances.

Nanorobots attack tumor using iodine isotopes

Researchers from the Institute for Bioengineering of Catalonia in Barcelona have learned how to use microscopic nanorobots to attack bladder cancer from the inside. A whole "army" of these tiny fighters are delivered inside the organ with the help of a catheter, and their ordered motion is ensured by urease - an enzyme that catalyzes the breakdown of urea into carbon dioxide and ammonia.

The breakdown reaction releases ions, the flow of which creates a pulse. It's minimal and undirected. But if a lot of enzymes are attached to the surface of microscopically small silicone spheres, those will start moving. The result is an "enzyme-driven" nanorobot (or nanobot for short).

In the bladder, where fuel - urea - is abundant, such nanorobots are able to travel certain distances. Hitting the smooth bladder wall they rebound, but get stuck in the rugged surface of a tumor.

Such local instillations have already become standard in the treatment of urothelial carcinoma. For example, the antibiotic mitomycin C, which has a cytostatic effect, or the tuberculosis vaccine BCG, which activates the local defense against cancer, are administered in this way.

However, both treatments have only a limited effect. In particular, most of mitomycin C and BCG are excreted from the body with the next urination. In addition, untargeted exposure to mitomycin damages healthy mucous membranes, resulting in numerous side effects.

The method presented by the scientists from Barcelona consists in delivering nanorobots, consisting of porous silicone spheres 450 nanometers in diameter and equipped with numerous urease molecules, into the bladder. The molecules provide the necessary driving force and are protected from decomposition by a special modification technology.

The weapon carried by the nanorobots is the radioactive iodine isotope I-124, a radionuclide often used in medicine. Its half-life is 8.02 days, which provides a sufficiently long period of exposure. At the same time, I-124 - beta-emitter has a short radius of action (about 0.8 mm), so healthy tissues near the tumor will not be affected. Nanobots are also equipped with a tracer for positron emission tomography so that its accumulation in the tumor can be observed from outside.

Researchers tested the treatment on mice infected with urothelial carcinoma cells. PET showed that after the nanobots were instilled into the tumor, their numbers increased eightfold. They penetrated into its deep layers, which the researchers were able to demonstrate using a specially designed fluorescence microscope.

Clinical trials are now needed to find out if this is enough to hold back the long-term progression of cancer.

In principle, the nanorobots could also be loaded with cytostatic drugs. Presumably, strong cytotoxins that are too toxic for systemic therapy could be used in this way. Clinical trials are also needed to determine the tolerability of such treatment.

Immunotherapy can preserve the bladder even with muscle invasion

For patients with carcinoma that has grown into the muscle layer but has not yet spread into the lymph nodes or other organs, complete removal of the bladder (radical cystectomy) is currently recommended. In many people, this procedure helps to cure the cancer.

Therefore, alternatives are being sought in which the bladder can be preserved. Previous studies have shown that neoadjuvant chemotherapy often leads to pathological complete remission: no more cancer cells are found in the removed bladder. So, in fact, radical surgery could have been avoided.

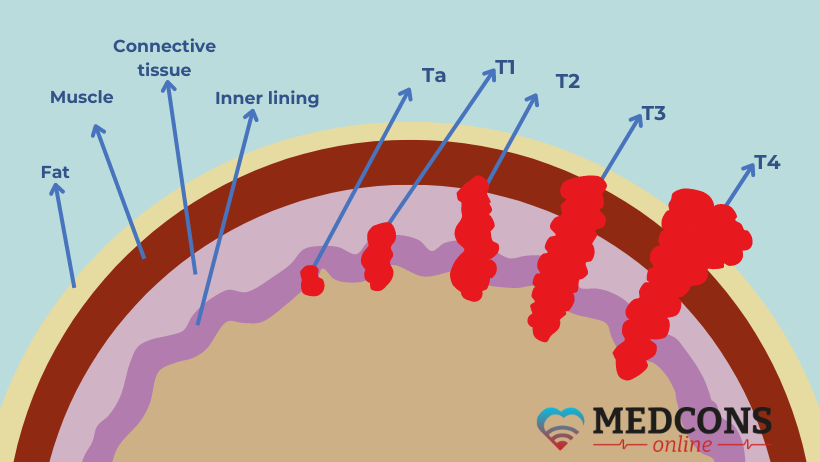

Doctors at the Mount Sinai Cancer Institute in New York City are currently investigating whether in some cases it might actually be possible to do without cystectomy. The phase 2 study initiated by physicians involved 76 patients with muscle-invasive bladder cancer in stage cT2-T4N0M0 (according to TNM classification), that is, without regional and distant metastases (see fig.1). All had the visible tumor removed by transurethral resection.

They first received four cycles of chemotherapy (gemcitabine plus cisplatin) with immunotherapy with the checkpoint inhibitor nivolumab. This was followed by restaging including biopsy, urine cytology and magnetic resonance imaging.

In 33 patients (43%), none of the findings showed evidence of cancer growth. It was suggested that they get eight more cycles of nivolumab rather than cystectomy.

32 patients agreed. Eight of them had a relapse 18-42 months later and underwent cystectomy. It turned out that in seven of these eight cases, the tumor had not spread beyond the bladder.

Another patient had a distant recurrence, and on the whole only two of the study participants developed distant metastases. After 30 months, the remaining patients can hope to be cured of their cancer without bladder removal, as experience has shown that recurrences usually occur in the first two years after chemotherapy.

Combination therapy for metastatic urothelial carcinoma shows promising results

Until now, the selection of first-line drugs for patients with metastatic urothelial carcinoma who are not eligible for cisplatin therapy has been a problem. Currently, alternative chemo drugs or checkpoint inhibitors (antibodies to PD-(L)1) have been suggested for PD-L1-positive tumors. However, the latter do not demonstrate sufficient efficacy in the presence of alterations in the fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR).

A group of researchers from the University of Texas at Houston evaluated the efficacy and tolerability of erdatifinib, an FGFR inhibitor, as first-line therapy for metastatic bladder cancer with FGFR alterations in a randomized trial.

The study enrolled 87 adult patients not yet receiving systemic therapy, for whom treatment with cisplatin was contraindicated. They were randomized in a 1:1 ratio to a group receiving erdafitinib monotherapy or to a group receiving combination therapy with erdafitinib and the PD-1 antibody cetrelimab.

The median follow-up time was 14.2 months. Response to therapy was found in 24 participants in the combination therapy group and 19 in the monotherapy group. Complete remission occurred in 6 cases with the combination and in 1 case with a single agent.

In both groups, 4 patients were PD-L1-positive. Of these, 3 (75%) responded to treatment with erdafitinib plus cetrelimab and none responded to treatment with erdafitinib. After one year, 68% of patients were alive on erdafitinib plus cetrelimab and 56% on erdafitinib.

Good tolerability of the drugs is also noted: co-administration did not lead to any additional toxic effects.

References

- Galsky, M.D., Daneshmand, S., Izadmehr, S. et al. Gemcitabine and cisplatin plus nivolumab as organ-sparing treatment for muscle-invasive bladder cancer: a phase 2 trial. Nat Med 29, 2825–2834 (2023).

- Simó, C., Serra-Casablancas, M., Hortelao, A.C. et al. Urease-powered nanobots for radionuclide bladder cancer therapy. Nat. Nanotechnol. (2024).

- Arlene O. Siefker-Radtke, Thomas Powles, Victor Moreno, Taek Won Kang, Irfan Cicin, Angela Girvin, Sydney Akapame, Spyros Triantos, Anne O'Hagan, Wei Zhu, Meggan Tammaro, and Yohann LoriotAUTHORS INFO & AFFILIATIONS. Erdafitinib (ERDA) vs ERDA plus cetrelimab (ERDA+CET) for patients (pts) with metastatic urothelial carcinoma (mUC) and fibroblast growth factor receptor alterations (FGFRa): Final results from the phase 2 Norse study. Journal of Clinical Oncology Volume 41, Number 16_suppl

Comments — 0